What follows is an interview with Chuck Surack, the founder of online music superstore Sweetwater. Chuck has a lot going for him. He's built a huge enterprise over the past 35 years that he owns outright, and he still loves what he does. In fact the Sweetwater enterprise is totally infused with Chuck's experience, world view, and belief that necessity is the mother of invention.

Although the interview took less than an hour a lot of ground was covered, so we're posting it in two parts. There are lots of interesting and instructional anecdotes about how to do things right in business, so read on and learn.

Although the interview took less than an hour a lot of ground was covered, so we're posting it in two parts. There are lots of interesting and instructional anecdotes about how to do things right in business, so read on and learn.

What were you doing before you started Sweetwater?

In high school I went down dual paths to do music and to be a doctor. I was a saxophone player, but I was also technical and I taught myself electronics. I was always the guy in the band that could run the mixer from the stage, and I actually made my own speaker cabinets and own mixers and compressors and amplifiers and all kinds of crazy stuff.

And after being on the road and playing all over the country for four or five years, I moved back to Fort Wayne in 1979 and started a recording studio in my VW bus.

So you were a mobile studio or you just liked the acoustics in your VW?

Yeah (laughs), mobile studio. I'd go out on location with my 1966 VW bus, which is kind of funny when I think about it, but I'd record bands at the local Elks Club, churches, schools, wherever, and I'd run the 200 foot snake into the building, mic up all of their instruments, and I'd sit in the bus with my headphones and initially a Tascam 3340 recorder. It didn't take very long and I upgraded to the amazing Tascam 80-8. We charged $22 an hour by the way, back in 1979.

As my recording business started to pick up, I graduated from the VW bus to the living room of my mobile home—I had a small 12x60 mobile home. I'd go out on location and record and I'd bring the recorder back into the mobile home. We'd mix down and maybe add a few other parts and that sort of thing. That grew into my first real commercial location. I built a studio that was about the size of a two-car garage at that point. This was the early '80s.

I was always into technology. I fixed my own recording gear. I made my own recording gear. I put new capacitors and IC chips in my equipment to have a faster slew rate, faster response and better signal-to-noise, lower noise. Then in 1984 I went with a friend to the NAMM show and saw the Kurzweil K250 and that just changed my world. I knew if I had one of those things, I could add other instruments to the recordings that I was doing.

I remember the 250 was about the size of a real piano...

I'd call it more like the size of a casket. It weighed 100 pounds. I had a Yamaha grand piano in my recording studio, and it was a great thing, but that sucker was out of tune all the time, and the only sound it did was piano. I rationalized that the Kurzweil K250 would do the piano sound plus the 38 other sounds that were in it, from acoustic bass to string section to vocal choir, and that sort of thing.

I sold the acoustic piano and bought the Kurzweil as soon as it became available. Not only did I use it in my own recordings, but at the end of the sessions, but I'd tell the artists, "Would you like to hear your music with an upright bass or a string section?" and I would end up booking additional hours of recording time just because I could enhance their music in addition to just recording it.

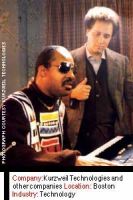

While I was doing that, I was also creating my own sounds for the K250. I started reaching out to other K250 owners and created the Sweetwater Sampling Network, with the idea of enhancing my own sound libraries by trading sounds with other owners. I got connected with Stevie Wonder, Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton, Lyle Mays, Bob James, and all of these artists, hoping to exchange sounds with them. What actually happened is they just wanted to use my sounds. So I'd give them my sounds.

Eventually I realized that with the Mac 512 I was using, the disk copy procedure was really painful—it would take something like 50 disk swaps to copy a disk. At some point, I said: "Uncle! I'm going to charge $5 a floppy disk." And customers would call up and buy literally every sound I had on floppy. I ended up buying another Mac just to duplicate disks. There weren't disk duplicators yet, or at least any that I could afford.

About the same time when something would go crazy on the Kurzweil and I'd have to fix it myself, like I did with all my other gear. So I reverse engineered how it worked and did my own addition sound blocks for it. The sounds that were originally on it were Mask ROM chips, so I figured out what the file format was and the structure of the thing, and using an EPROM blower I put my own sounds into EPROMS.

The other thing was that the K250 had a two-line display, which made working the way I wanted to work cumbersome. So with a friend I wrote a Kurzweil K250 editor/librarian. All of the K250's button presses were sent over MIDI, so using external MIDI messages, all of the sudden what was on the two-line display could show up on the beautiful nine-inch Mac display. Splitting keyboards to put bass on the left hand and piano on the right hand or layering sounds, all of those things that were difficult using a little two-line display, became much more visual on the nine-inch Mac.

Did you learn how to program in C or did you use some other kind of language?

It was all done in C. I did it with a buddy of mine. He did more of the coding, but I knew the Kurzweil and I could turn it into English so he could turn it into code. I wrote the manuals and I figured out how to make everything the Kurzweil's display did come out over MIDI, so I figured out how to interpret that MIDI and make it talk to the Mac and basically use what was called Macintalk way back then.

Because the Kurzweil was designed for Stevie Wonder, it was very tactile. You could physically feel every button. Nothing was more than one layer away. It was really, really fast for blind people to get around on, and with my talking display, I could make the sequencer literally say, "One, two, three, four." Everyone that bought a Kurzweil was coming to me for accessories and options and I got the reputation of being the guy that knew the K250. That was a big turning point for me.

The beautiful thing about that Kurzweil was that it was "works in a drawer." You could open it up and there were empty sockets to add additional ROMs from Kurzweil, or to add additional sampling. You could buy a two meg sampling set for like $10,000 or something insane in today's numbers.

I went to an AES show in New York, found the Kurzweil folks, and said: "Has anyone ever done another block of sounds for this?" and they crossed their arms and said "It couldn't be done because we use our own system and millions of dollars of proprietary computer software," and blah, blah, blah. I said "Well, you want to plug this in?" and they looked at me and just about passed out because I had a cartridge that had ten EPROM chips in it. They plugged it in and one of them said, "No, we can't do that at the trade show. We don't want to hurt our machine." Eventually they learned that I knew what I was doing and from that point on I had their respect.

I became a Kurzweil dealer, to go along with my recording studio. Then one day a friend called me and said "I understand there's software that can show sheet music on your Macintosh" —Mark of the Unicorn had come out with Professional Composer. I became a dealer for that, and then computer interfaces, and by 1990 I had five people working in my home, coming and going at all hours, night and day, and so forth.

What inspired you to set up the support infrastructure within Sweetwater? Obviously, it was in your DNA.

It was in my DNA, and being a recording studio in Fort Wayne, Indiana, there weren't technicians around like in LA, Nashville, or New York City. I had to learn how to read circuit diagrams and troubleshoot when a part blew up or whatever, so I always had to support myself. And then I took care of my friends.

I remember one time in the '80s I was going over the bridge from Detroit into Canada. I got a call from a customer in New York and his Kurzweil wouldn't fire up. He was panicked because he had a big-time concert coming up in an hour. So I looked in my little Microsoft Works database and found another customer who was two blocks away from him. I said, "Call this guy. I bet he'll come help you." Sure enough, he helped him and the show went on. To me, it's all about support. I want to treat other people the way I want to be treated, and that's what we do today.

Who was your primary competition at the time? This is an optional question because some people don't like to talk about competition...

No, I think it's a good question. When I started my studio, you could go to the local music store and buy a TapCo mixer or a Crown D60 power amp, and those sorts of things. But man, in the Midwest, there weren't dealers that were carrying the products that I wanted in my studio.

Equipment was very expensive, so a lot of the stuff, I either had to make myself or, as I got more into the retail side of things, I just became a dealer for whatever I needed. Or you'd get in a car and go to Chicago or find a way to get to New York. Of course, there was Sam Ash, and Gary Gand was in business at that time up in Chicago, but most technology places were broadcast radio station oriented. Traditional music stores were selling band instruments and pianos. Nobody understood or was interested in technology.

So, when you needed stuff for your studio, you had to drive to Chicago?

Absolutely. I bought tons and tons of my stuff in Chicago from a place called DJs, which is now out of business. There was another place called Flanners Pro Audio, which is now also out of business. In the early days I did business with Full Compass. I bought lots of cassette tapes and some recording gear from them. There was nowhere around Fort Wayne to get it.

You guys were one of the early places where you could buy the product for a lower price, and then of course you built a huge infrastructure for support, so I'm wondering which of those things has been the most important to Sweetwater's success?

We're always competitive in price, but I've never been the low-ball guy, because I can't afford to be with the level of service that we offer. I've always wanted to provide the best value, and value, to me, is more than just price. Value is that you're there to take care of the customer, short term and long term. When someone bought a synthesizer from us, they got the machine, they got me or one of my helpers to be there to answer questions, and they got an additional pile of sounds from us. You got some of the Sweetwater sound libraries, the same sounds that were on Stevie Wonder's albums or Kenny Rogers' albums.

I now have a guy here at Sweetwater whose job is to find ways to add value to the products that we sell. If it's a keyboard, that may mean additional sounds. If it's a set of speakers, it may be a guide to how to set those speakers up. He writes custom manuals and all kinds of extra help tools, so you get more value.

Back to your question, to me it really is all about the level of service and support and people knowing what they're doing. It's being realistic on the price. Why would a customer buy from you if you're not offering a legitimate, real service or real value? Just being in a location or in proximity to me doesn't mean you have earned my business.

Obviously the Kurzweil K250 would be there, but are there any other products that you would like to give a shout out to?

I've owned most of the popular electronic stuff since I started in 1979, and of course, like most of your readers, I've sold it when the next new, bigger, badder thing came out. Just in the last three or four years I've been trying to gather many of those things I used to own. Some day we hope to maybe have a little museum here at Sweetwater.

Anything that was breakthrough in its time is impressive to me. An example is TASCAM with their reel-to-reels—they went to half of the width of tape but with the same number of tracks. All of the sudden you could buy a half-inch eight track or a one-inch sixteen track. That was pretty revolutionary to me. The Linn Drum was incredible.

And, believe it or not I actually owned a Synclavier for 30 days. I only owned it for thirty days because it was also a nightmare and a disaster in the next breath. After having the K250, the Synclavier was sold to me on the concept that it had hard disk recording in it, so I was doing a lot of radio jingles and I could slice and dice various parts of the music to go much faster. That was the first hard disk recorder I ever owned.

But the other thing—probably even more powerful to me than the hard disk recording—was that it was very tactile. With all of the buttons and switches you could arm tracks in the hard disk recorder from the front of the keyboard. It was one of the first remote-control units or control surfaces, like a serious MIDI controller, with controls for fast forward, rewind, play, record, arm tracks, to load a new sound.

The second thing that was interesting about it, was that it was tightly integrated with a Mac 2 computer—actually a Mac IIFX at the time. That itself wasn't much because they didn't really use the Mac very well. They had their own Able computer. But what was interesting about it is that they required it to be sold—and you've got to understand, this is '86 or '87, something like that—they required it to be sold with a two-page display. At that time, two-page displays were wickedly expensive, but the value of the screen real estate and the value of the tactile buttons were huge for me. I've used those two ideas in my company ever since I bought that Synclavier.

So to me the Synclavier was just an amazing thing. But again, it was also a disaster on a bunch of technical levels and the company obviously went out of business. They definitely were on the bleeding edge from an interface standpoint—hitting the buttons and seeing the display easily instead of scrolling through lots of pages and screens. They really took "user interface" to a new level.

Other Related News

Other Related News